As the weather turns cold, the best season arrives—perfect for snuggling up and indulging in the greatest art form of all time: films. This time of year, as one chapter ends and a new one begins, is ideal for reflecting on what we’ve been watching during these joyful hours.

The big finale of 2024 in theatreland is Harbin (2024), a somber portrayal of An Jung-geun, an independence fighter and leader of the Righteous Army—an army of ordinary people. An Jung-geun is etched into Korean history as the man who assassinated Ito Hirobumi, the first prime minister of Japan, at Harbin Station in 1909. His final words in the prison at Lushun before his execution offer a glimpse into his motivations: the essence of being human lies in sacrificing for a greater cause.

The reception of Harbin has been divided, with some finding it “too dark” while others praise it as “insightful.” The film appears to continue the trend of recent big-budget productions such as Assassination (2015), The Age of Shadows (2016), Hero (2022), and Phantom (2023), all set in the colonial era to explore the stories, glory, and predicaments of independence fighters. Is this a new trend, or has it always been a part of our storytelling?

What follows is a look back at a selection of films released during the holiday season in December from each decade: 1974, 1984, 1994, 2004, and 2014. The trajectory reveals some intriguing changes.

1974 – The Wildflowers in the Battlefield

In December 1974, Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949) and the children’s adventure film Benji (1974) were shown in theaters. The re-release of epic biblical films was not uncommon—Ben-Hur (1959) graced theaters five times until 2019. Moreover, a significant portion of Christmas TV programming in the 1970s was dedicated to movies based on biblical stories.

The Wildflowers in the Battlefield is a large-scale war drama that chronicles the Korean War from the perspective of Captain Hyun, whose company is part of the border defense near the 38th parallel, geographically close to the contemporary DMZ (Demilitarized Zone). The film begins with North Korean tanks advancing in rows, invading the border and rapidly pushing the war front southward.

For children who grew up in the aftermath, the North Korean tanks that overwhelmed the South Korean defense became a horror story—a haunting reminder of a war that left South Korea nearly in ruins. Today’s children, however, might tremble at a different horror story: the massacres of communists and communist sympathizers during the early years of the war, as depicted in the 2004 film Taegukgi.

The Wildflowers in the Battlefield is neither defeatist nor triumphant in tone, nor does it solely arouse patriotic sentiment. Instead, it focuses on the profound value of peace, family, and tradition for the Korean people.

1984 – Hunting of Fools

Arguably not fitting the bill of the festive season, Hunting of Fools is a surreal dark satire centered on two madmen who escape from a mental hospital to pursue their dream of finding a paradise island. On this island, they believe, rabbits that do not drink water and bees will provide their subsistence. Paranoid maniacs, they are convinced that the entire world is corrupt and polluted. Once released into society, however, they find that what they encounter is not far removed from their delusions.

Much like the mental asylum patients who appear surprisingly ordinary in a small French town abandoned by the German army near the end of the First World War in King of Hearts (1966), the madmen in Hunting of Fools blend seamlessly into the modern landscape of Seoul. The film was written and directed by Kim Ki-young, whose masterpiece, The Housemaid (1960), profoundly influenced a generation of Korean filmmakers. The Housemaid carries an unsettling, psychotic undertone, delving into the psyche of a housemaid who attempts to alter the course of her life by seducing the man of the house, provoking jealousy and chaos within the family. Hunting of Fools oscillates between psychotic madness and sharp satire, offering a singular and provocative cinematic experience.

1994 – How to Top My Wife

This is one of the most beloved comedy films of the 1990s, featuring a standout performance by Choi Jin-sil, often considered Korea’s answer to Meg Ryan. Choi rose to fame by seamlessly blending the charm of the girl-next-door with the savvy, on-trend appeal of a modern woman. She was also regarded as the queen of TV commercials, driving sales for household appliances produced by the electronics company that has since become a world-class smartphone maker and chip supplier.

In the film, Choi plays an executive at a film production company who is married to a cheating husband—who also happens to work at the same company. Desperate to end the marriage without the disgrace of a scandal, the husband devises a plan to kill his wife and hires a hitman. However, every attempt to get rid of her hilariously backfires.

While the plot might sound grim, Choi, along with her comedic partner Park Joong-hoon, skillfully turns the dark premise into a source of laughter, delivering an unlikely but highly entertaining comedy.

2004 – Rikidozan: A Hero Extraordinary

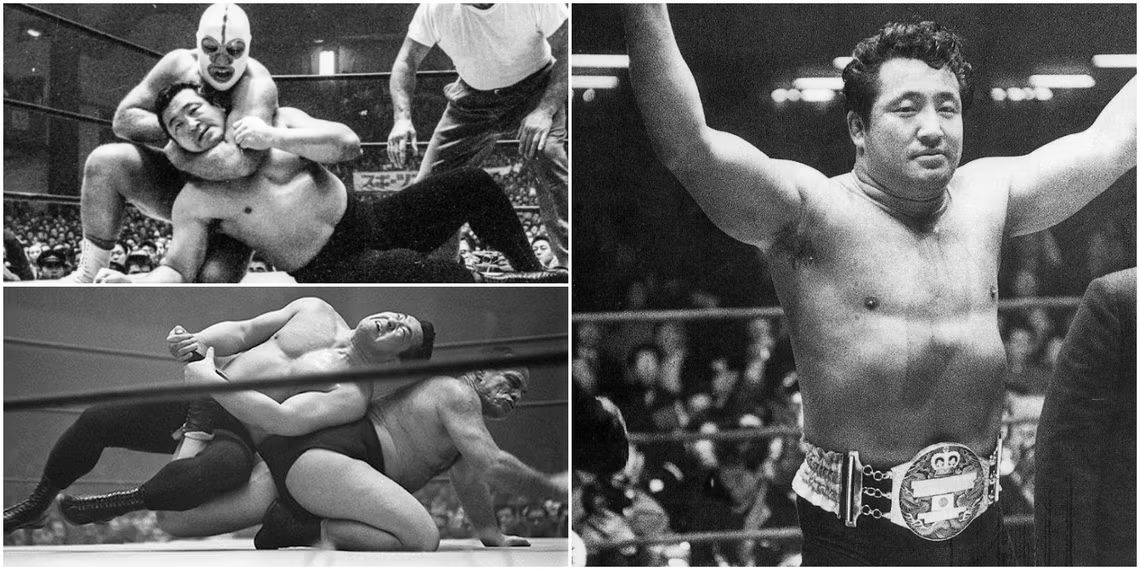

This biopic tells the story of Mitsuhiro Momota, better known by his nickname Riki, or Rikidozan, which means “arts of power.” He was a first-generation pro wrestler and is regarded as the father of Japanese pro wrestling, almost synonymous with the sport’s boom in Japan during the 1950s. Born in Korea, Riki moved to Japan at a young age, where he initially pursued Sumo wrestling. However, unable to become a champion due to Sumo rules that allowed only natural-born Japanese to claim the top rank, he transitioned to professional wrestling.

In the wrestling ring, Riki personified the Japanese spirit of resilience, embodying the struggle to overcome hardship for his adoring post-war Japanese fans, who still vividly remembered the defeat of World War II, its devastating aftermath, and the American occupation. His matches against the Sharpe brothers were instrumental in cementing his legacy, turning his bouts into dramatic spectacles on the four-cornered ring.

The film could have explored Riki’s identity as a Korean-born Japanese grappling with his place in a society riddled with ethnic and racial discrimination. It could have easily evoked nationalistic sentiment among Korean audiences by emphasizing the historical context of Japanese colonial rule that shaped Riki’s life. Instead, the film focuses on his personal journey and contributions to the emerging sport-entertainment of professional wrestling.

The scene where he cuts off his Sumo wrestler top knot and declares, “I decide my own fate,” serves as a symbolic moment for the entire movie. Considering the rise of Korean blockbuster films in the 2000s, many of which leaned heavily on themes of national identity or pride, Rikidozan: A Hero Extraordinary stands out as a peculiar and distinctive piece.

2014 – Ode to My Father

Ode to My Father revisits the Korean War and aligns with the thematic trend of recent big-budget films. While its story spans from the war to the present day, it emphasizes the enduring value of family. The film begins with one of the most dramatic moments of the war: the massive evacuation of North Korean civilians and UN forces from Hungnam Port to Busan, South Korea, aboard warships in December 1950.

The narrative unfolds around a family who loses their youngest daughter during the evacuation. The story reaches its emotional climax in 1983, when the family is reunited with her through a TV program dedicated to reuniting families separated during the Korean War.

While selecting one film per decade over the last fifty years may not fully capture trends in Korean filmmaking, it suggests that historical memories such as the Korean War and Japanese colonial rule have regained pertinence, particularly through big-budget films since the 2000s. These memories appear to influence the direction of the nation’s cinematic storytelling, engrossing Korean audiences in the narratives of modern Korea.